THE CROWD-DEVICE

From the Birth of Crowd-Funding to Its Inversion into Digital ID & CBDC

(Public Statement)

1. Introduction

The Crowd-Device is now a universal civic-participation mechanism developed across three decades by ‘British Invention of the Year’ Award Winning British inventor Paul A. Sparrow. It did not appear fully formed, nor was it conceived as a grand civic system. It emerged naturally, step by step, and it evolved into full spectrum of domains and wrappers that give ordinary people the ability to influence real-world outcomes without needing approval, capital, access, or permission from institutional gatekeepers.

The device was, from its very first expression, a public-from-home mechanism — enabling widespread participation without physical gathering, studio environments, or institutional mediation.

What began in 1992 as a simple public-funding mechanism eventually revealed itself — through struggle, obstruction, innovation, and lived experience — to be a four-domain civic operating system. By 2020 the structure was complete, and in 2025 its authorship and rights were formally restored. The Crowd-Device is now understood not as a business model or a single invention, but as the foundation of an entirely new era of public capability, unity, and self-governance. Essentially, the Crowd-Era!.

2. The Beginning (1992–1995)

The Funding Domain Emerges

The earliest expression of the Crowd-Device appeared in 1992–1993, when Paul Sparrow attempted to fund his Peter Pan Adventure Board Game — invented as Pirates Quest in 1989, and developed into Peter Pan in 1993 — through a national mail-order campaign. The model invited the public to participate from home, pledge support before production, respond collectively, and unlock or halt the project depending on whether a public threshold was reached. This philosophy also allowed creators to test market their ideas prior to laying out expensive production setup costs. Refunds were guaranteed if the target was not met.

This flyer demonstrates the year of 1993, and that no cheques will be cashed until the game is shipped. This was the initial attempt to pre-sell the product to raise production funding from customers directly.

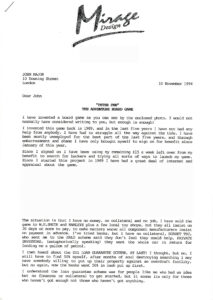

But this effort was blocked by the discovery of ‘Forward Trading’ regulations which stated that a product could not be advertised if it did not already exist, as it had to be delivered within 30 days or be subject to full refunds. Out of utter disbelief that every avenue he turned to in the hopes of finding a way forward, he would hit yet another brick wall, and in (1994) Sparrow vented this to the then Prime Minister John Major with an outpouring of frustration.

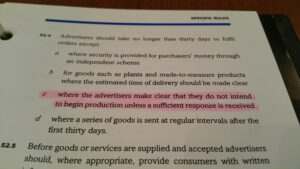

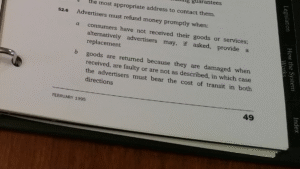

Unperturbed, this set-back prompted Sparrow to undertake what would become a two-year fight for regulation change, as he felt the concept was just too good an idea to allow it to slip into the abyss when it had so much potential to change the financial landscape for those that fall through the cracks, and his efforts with MOPS, the Mail Order Protection Scheme, eventually resulted in the addition of Clause 52.4(c) to the UK advertising code in 1995, a reform that legalised pre-production funding thresholds and later became the foundation of all modern crowdfunding.

This last image above shows the date of publication, and demonstrates that this clause was the turning point. Without this reform, the Crowd-Device invention would have ended here.

This early form of the mechanism demonstrated something historically significant: Sparrow conceived in 1992, through simple postal responses, the same behavioural architecture that later digital systems required the internet, broadband, smartphones, and streaming to deliver. This shows the concept did not arise from technology — it arose from the structure of the mechanism itself. Modern platforms merely revealed the same pattern with newer tools, confirming that Sparrow’s original framework contained the full behavioural logic decades before the world adopted it.

Sparrow continued to seek investors and also appeared in a local Newspaper still seeking funding for his board-game.

3. 1996–1999

The Peter Pan Submissions and the First Major IP Theft

After the 1995 reform, Sparrow continued pushing his Peter Pan Adventure Game forward. In January 1996 he submitted a proposal to transition his board-game into a TV game-show — sending out copies of the board-game to accompany his proposal to multiple parties, including the BBC, ITV, LWT, Planet 24, Action Time, Mentorn, and several others.

On 1 May 1996, Planet 24 — owned by Charlie Parsons, Lord Alli, and Bob Geldof — formally rejected the proposal, saying he needed a partner with more experience in making TV Gameshows.

But in 1997, Planet 24 launched Expedition Robinson in Sweden, which carried the same structural DNA found in Sparrow’s Peter Pan board-game: survival, strategy, conflict, hazards, immunity, skullduggery, and resource management. When the format moved to the US, it became Survivor (2000), one of the most successful global entertainment formats in history, which also led to the creation of The Apprentice, which itself went on to help seat a US President.

This event marked the first time Sparrow experienced what would become a repeating pattern in later years:

a submitted concept rejected, then re-emerging as a major commercial format, uncannily produced by the same people that had previously turned him down.

Parallel Interest from Broadcasters

At the same time, his Peter Pan game-show concept also received independent interest from regional television.

Westcountry Television expressed interest in viewing a pilot if he made one — confirming the concept had commercial and broadcast viability long before Planet 24 converted Sparrow’s board-game into a global franchise. Sparrow had conceived two versions, one Studio based, the other on a real Island. Regardless of final format, he proposed a joint venture with the clear expectation that adaptation would be required.

The Shift Toward New Concepts (1996–1999)

In parallel with the events of 1996–1997 with the board-game, Sparrow began developing another new innovation-centric TV format which started as Tycoon in 1996, and evolved into I Did This 1998 and later Brainwaves also in 1998.

These concepts incorporated:

- real inventors,

- the Inventor’s Whipround, a broadcast-donate/vote-from-home iteration,

- the first “live pitch” concept ever proposed for television, later forming the format of the BBC’s Dragons’ Den (2005), the US Shark Tank (2009), and other derivatives around the world, starting with Money Tigers in Japan (2001).

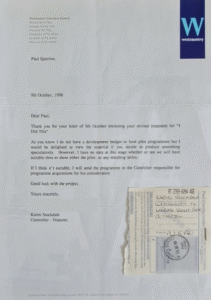

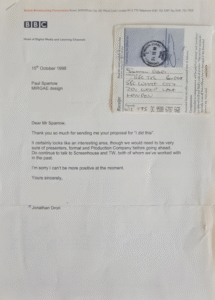

Each variant was submitted to broadcasters in their respective development years, and one of the following 1998 reply later resulted in a meeting at BBC HQ in May 1999, and the show almost got picked up by BBC2 for March 2000, for their Millennium schedule.

This shows that two broadcasting channels considered this project viable.

Sadly this contact changed roles within the BBC a few months after this meeting and the interest went cold.

The collapse of broadcast interest pushed Sparrow back toward independent development. With no institutional route forward, the only path remaining was to build his own public-driven platform — a decision that directly led to the development of the Octopus Initiative and the PLP.

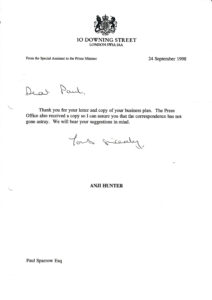

The No.10 Downing Street Interaction 1998

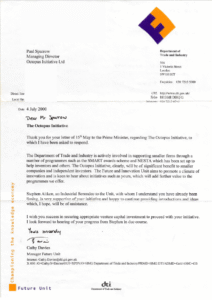

During this period, Sparrow also proposed the Crowd-Device system to No.10 Downing Street. The model was formally reviewed as a potential national mechanism for increasing public participation in innovation.

It was the first moment the Crowd-Device entered the political environment surrounding Prime Minister Tony Blair — a detail that would later become significant as Digital ID frameworks grew to mirror inverted versions of the same behavioural architecture.

BBC Rejection and the Move Toward a Platform (1998)

In the meantime Sparrow continued to submit Brainwaves to broadcasters and also re-approached the BBC.

This image alone demonstrates that all three TV concepts originated from the same person in the same time period.

With broadcast routes blocked again — echoing what had happened with Peter Pan and Planet 24 — Sparrow turned his attention back to the deeper structure of his public-participation idea.

This shift laid the foundations for what would become the Octopus Initiative and its embedded Product Launch Platform (PLP).

4. 1999–2002

Hidden Domains Reveal Themselves

With the legal barrier now removed, Sparrow focussed his attention back to the Crowd-Device and refined the mechanism further. Although designed purely as a funding tool, the mechanism already contained the same structural logic that would later define the Crowd-Device’s internal mechanic across two additional domains:

- a token, the remote public response (Donation),

- a threshold of participation (Target),

- an outcome triggered by collective decision (Proceed or Fail).

These two additional domains — Voting and Action — were already operating inside the 1992 funding model, yet they all used the same mechanic without alteration. At the time, Sparrow hadn’t yet recognised them as separate domains, and lacked the conceptual framework to describe what he had built; the structure however, clearly existed years before it could be properly articulated.

The first was public choice. Each mail-order response effectively became a remote vote. If enough people responded, the project proceeded; if not, it was cancelled. The public, from their homes, were functioning as the deciding authority. The Voting Domain was already there, embedded within what appeared to be only a funding process.

The second was shared public-driven execution. Every individual or organisation could collaborate labour and resources to achieve a pre-defined action — renovating a public building or shared space, sharing tooling and production of a new product are prime examples. This was the Action Domain in primitive form. Sparrow saw the behaviours, but without a computer capable of organising the complexity, the emerging architecture could not yet be expressed.

Only in later years, as platforms like Kickstarter, GoFundMe, X-Factor, and large-scale digital polls emerged, did the full structure of the early mechanism become unmistakable. These later systems did not influence the invention; they merely revealed, in hindsight, that Sparrow’s 1992 framework already contained the core behavioural architecture long before the world adopted it.

The Incorporation of Octopus Initiative Limited and the First Online Platform

In 1999, when Sparrow purchased his first laptop, the deeper pattern finally became expressible, the underlying structure of the mechanism could at last be examined in its full depth.

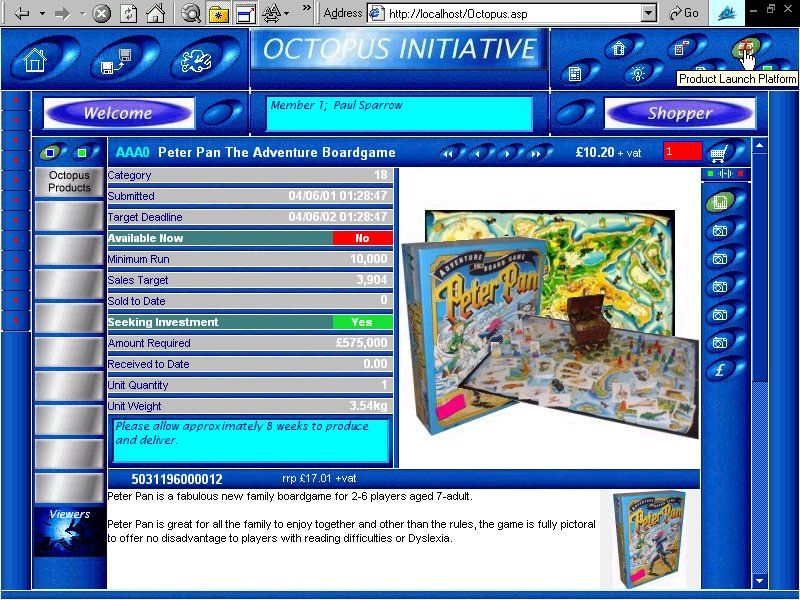

The new Octopus Initiative company (1999) represented the first attempt to bring the system online. The PLP (Product Launch Platform) became the first digital prototype of the Crowd-Device’s structural engine.

This screenshot of that original development clearly shows all the required mechanics seen in all subsequent modern crowdfunding platforms such as ArtistShare, Kickstarter, IndieGoGo and GoFundMe. The PLP was online between 1999 and 2002.

Government Secondee Assigned 1999 – 2002

As part of the national-scale interest from No.10, a senior DTI secondee was assigned to assist Sparrow in developing an online public-participation platform.

This support ran in parallel with his attempts to commercialise Brainwaves, and stands as formal evidence of government-level engagement with the early Crowd-Device architecture.

As global media, online platforms, and public-interaction systems evolved, the same underlying mechanics began appearing in multiple industries. Rather than diminishing his originality, these echoes clarified the depth of the original invention by making its structure visible in retrospect.

The Three-Domain Stage Becomes Visible

The three later emerging domains were not “newly created” at this stage — they had been present since 1992, operating invisibly inside the Peter Pan funding model. Yet even here, the drafts were still framed around a funding-first perspective. The PLP focussed on pre-order funding, public proposals, and early-stage investment — not because the other domains were absent, but because Sparrow had not yet realised that these processes were, in fact, three separate forms of public power operating together: public-driven funding, public-driven choice, and public-driven action, and each widened the horizons of the overall concept far beyond merely raising funds without altering the mechanic itself.

Only later, when the world began producing its own versions of the same behaviour — X-Factor voting cycles, Kickstarter campaigns, audience-driven interactive formats, social-media likes and polls, and ultimately Digital ID and CBDC behavioural gating systems — did the full picture come into focus. These later derivatives confirmed what Sparrow had not consciously articulated at the time: that these domains were fundamental public Crowd-Device behaviours, not features bespoke to each single product.

The mechanism already existed.

The architecture was already present.

What Sparrow lacked in the 1990s was not invention — it was the vocabulary to describe what he had built.

Recognition came retrospectively, not because the system changed, but because the external world eventually made its own copies. And once those copies became visible, it became clear that origin, authorship, and structural ownership had existed from the beginning, even though Sparrow did not yet know that his rights endured and survived over time.

5. 1999–2025

The Platform Years — BizKit-Tin, X-Pro, and the Long Road to the Fourth Domain

Once the three-domain structure was articulated, Sparrow spent the next two decades trying to turn the mechanism into a functioning online platform. This period was defined by a repeating structural problem: every route to market required institutional permission and external investment, and every institution demanded conditions impossible for an unsupported inventor to meet.

5.1 Octopus / PLP (1999–2002): The Unfinished Prototype

Sparrow attempted to build the online platform himself. He was not a programmer, developers refused to work without salary, investors refused to invest in unbuilt systems, and no one understood the concept well enough to speculate on future value. After three years, the prototype had to be taken offline—not due to conceptual failure, but because ordinary people cannot innovate within systems that demand institutional permission at every stage.

5.2 Return to Trade (2002–2005)

Unable to secure development support, Sparrow returned to his trade as a window fitter. He continued building drafts, refining the idea, and attempting to secure funding. The world had still not caught up with public-driven systems.

5.3 Shift to X-Pro (2006–2012)

The same catch-22 that blocked the Board Game now re-appeared. Retailers demanded stock before placing orders. Banks demanded retailer orders before lending. Manufacturers demanded deposits before producing stock. Sparrow revived his PLP concept, rebranded it BizKit-Tin, and spent seventeen months slowly gathering pre-orders from ordinary supporters.

BizKit-Tin is a public-driven model designed to create a central funding pool to which creators can apply for equity investment, allowing the fund to grow from successful investment projects. It has no shareholders, so all profits go back to the fund, save for an admin fee to run the fund and an inventor estate commission.

By 2014 he raised enough to manufacture X-Pro Levels, which debuted at the International Hardware Fair in Cologne and secured Toolstation as its first major retailer.

5.4 Distributor Suppression (2014–2017)

Toolstation guided Sparrow to their preferred distributor, ForgeFix (Toolbank). This became the single most destructive point in the entire commercial phase. ForgeFix bought the entire production, failed to place it in any catalogue, misrepresented retailer interest, and ultimately suppressed the product by ensuring the market believed no stock existed. Sparrow exposed this collusion in a 2017 video of recorded meetings. Retailers confirmed they had been told the product was not stocked. [Insert video link]

This was not failure. It was deliberate obstruction—and it revealed the final missing domain.

5.5 The Epiphany: Crowd-Distribution

Sparrow realised that even if the public funds, chooses, and carries out an outcome, institutions can still kill it in the final stage by controlling distribution. This insight birthed the fourth domain: a public-led distributive structure capable of bypassing retail choke-points entirely. Through micro-warehousing, pre-distributed custody, and public-driven routing, the Distribution Domain completed the architecture.

5.6 Blacklisting and Closure (2017–2019)

After exposing the sabotage, Sparrow was effectively blacklisted. He continued selling online but was locked out of the industry. His company, created originally to launch the Crowd-Device, eventually closed its doors in 2024. The X-Pro patent was retained regardless.

5.7 u-Reka (2020–2024)

The discovery of Crowd-Distribution revived the platform, now renamed u-Reka. Despite crowdfunding becoming mainstream, investors and developers still refused to support an unbuilt system. No off-the-shelf tools could handle the mechanics. The platform was eventually placed into Maintenance Mode, awaiting future funding.

5.8 Discovery of Global Inversion

During this period Sparrow realised something far more profound: the Crowd-Device had been inverted and weaponised within global Digital ID systems. Where he designed a public-empowerment engine, governments had mirrored the architecture to create behavioural gating systems—counting tokens not to empower communities but to control individuals. This discovery led directly to the Illegitimacy research, the recognition that sovereignty had already reverted to the people, and the creation of the Phoenix Charter.

5.9 Summary

Between 2003 and 2020, Sparrow encountered financial exclusion, institutional refusal, deliberate sabotage, strategic betrayal, and industry blacklisting. Yet each obstruction resulted in a new evolution—BizKit-Tin, X-Pro, Crowd-Distribution, u-Reka, the Phoenix Charter—until the architecture was complete.

6. The Distribution Domain (Definition and Purpose)

For many years, even Sparrow did not fully recognise the scope of what he had built. Only in 2020 — after discovering deliberate suppression of his X-Pro Levels and seeing how distribution gatekeepers could strangle innovation — did the missing fourth domain become visible. That betrayal exposed the gap the public had to own: Crowd-Distribution.

The Distribution Domain is the fourth structural component of the Crowd-Device. It exists independently, alongside the other three domains, and completes the system by eliminating the final point of institutional control: the last-mile delivery of outcomes.

While Funding empowers the public to support something, Voting empowers them to choose something, and Action empowers them to work together to make something happen, Distribution empowers them to decide where outcomes go, how they are routed, and who can access them—without depending on retailers, distributors, wholesalers, or gatekeeping intermediaries.

It decentralises custody, removes chokepoints, distributes authority, and ensures that public-led outcomes cannot be buried by institutional actors. The Distribution Domain transforms the system from a dependent mechanism into an independent civic-economic engine capable of supporting communities globally, collaboratively, and without borders.

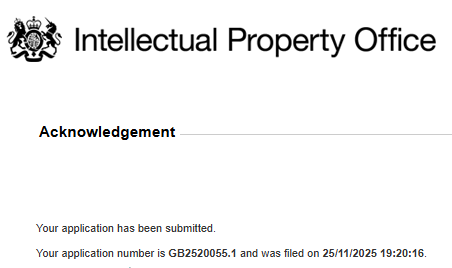

7. 2025: Rights Restored by Formal UK IPO Filing

Filed as GB2520055.1 on 25 November 2025, the UK IPO recognises Paul Andrew Sparrow as the originator of the Crowd-Device and restores all relevant rights across its entire developmental lineage.

7A. Authorship Rights

Permanent recognition as the creator across all drafts, versions and iterations from 1992–2025.

7B. Ownership Rights

Ownership of the four-domain architecture, explanatory documents, models, diagrams and behavioural logic.

7C. Moral Rights

Permanent and non-waivable protection against distortion, inversion, false attribution, harmful application and weaponisation.

7D. Evidential Rights

Authenticated origin date, admissible legal standing, certified public record and international recognition.

7E. Enforcement Rights

Authority to issue take-downs, enforce attribution, demand corrections, remove corrupted derivatives and escalate disputes to legal or regulatory bodies.

7F. Public Authority

Standing to issue public notices of misuse, inversion, misrepresentation or public harm — declarations that now carry legal weight.

7G. Rights Over Derivatives

Protection against structural, behavioural, architectural or functional copying across digital platforms, voting engines, participation systems, identity-linked systems, AI selection models and CBDC-linked control structures.

7H. Policy and Governance Intervention

Standing to participate in parliamentary processes, public consultations, inquiries, digital-governance hearings and human-rights contexts.

7I. Reassertion of Purpose

Authority to define correct use, reject inverted use, correct false narratives and embed ethical boundaries into trust or governance frameworks.

7J. Future Legal and Constitutional Rights

Ability to seek statutory custodial protections, constitutional embedding, international frameworks and legislative monopoly restoration.

7K. Licensing and Succession Rights

Rights to license the system, receive income for authorised use, define acceptable applications, pursue damages and transfer rights to the estate.

7L. Operational Authority

Authority to publish definitive versions, protect integrity, expose harmful derivatives, set ethical standards and establish a Perpetual Public Custodial Trust.

8. Custodial Intent

Paul Andrew Sparrow intends for the Crowd-Device to be placed into a Perpetual Public Custodial Trust. The Trust is active from the moment of its creation, ensuring that no corporation, government, institution, or elite can weaponise or monopolise the system. Only the restoration of monopoly protections requires a People’s Parliament. All other custodial powers remain active regardless of political circumstances.

9. Restoration of Monopoly Rights

A sovereign People’s Parliament may, by legislative act, restore statutory monopoly protections, place the system under perpetual custodianship, and ensure it remains a public-owned civic asset. This restores rightful revenue, operational funding for the Trust, and long-term protection for the public good.

10. Final Statement

The Crowd-Device did not emerge overnight. It grew across decades of invention, obstruction, revelation, and renewal. It began as a funding mechanism, revealed itself as a voting and action engine, completed itself through Distribution, and now stands as a universal civic system—one intended for empowerment, not control.

Its authorship has been restored. Its purpose is clear. Its future belongs to the people.